In my newsletter recently, I’ve been exploring the creation, distribution, and enforcement of digital property rights for players.

This requires looking at videogames from an unusual angle, through the lens of value creation and value transfer, which inevitably leads into the notoriously murky waters of game design. This article is an attempt to document the model I’ve come to use whenever I need to evaluate game design, partly to help clarify my own thinking and partly in the hope others might find it useful too.

In my last article I began considering the creation and transfer of value within videogames by using Atari’s Pong as my reference point. The first insight I highlighted was a deliberate choice Atari made to charge 25 cents per game rather than, say, $1 for a 30 minute session.

I consider it important to recognise that Pong’s value proposition (“Play a game of Pong for 25c”) was a deliberate design choice Atari made rather than some inalienable aspect of Pong that negated the need for any decision about payment terms to be made. That’s because it shows value creation is a function of design choices made by game designers: i.e. value creation is a subset of game design, which I’m not sure is a view that would be widely accepted within game development circles today.

In short, 25c per game was a design choice Atari made, just like whether the bats should be 8, 16 or 32 pixels in height, or whether 5, 10, 15, or 20 points should be the winning score. This illustrates a subtle aspect of game design that I think is worth making explicit here, because I don’t believe it’s especially well understood.

I still find the term “game design” as it applies to videogames somewhat poorly defined for my purposes. It’s often used much more broadly than for decisions that relate specifically to the rules determining how a game plays. Instead it is typically used as a general, catch-all term for the complete set of decisions a game developer makes to arrive at a self-contained interactive entertainment experience. Furthermore, if that videogame is intended to be made available on any sort of commercial basis then “game design” will likely also encompass any decisions related to how the game will be priced or charged for.

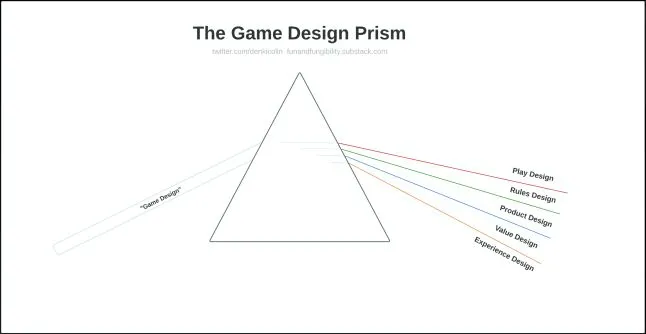

As a card-carrying scientist, I see that as an overly broad range of design decisions with a lot of potential for confusion and ambiguity. Therefore, I prefer to think of “game design” as the white light of a Game Design Spectrum. In the same way one can shine white light through a glass prism to reveal all its constituent colours, one can also pass game design through a game design prism to reveal all its constituent design elements.

In practice that reveals way too many types of design to enter into a detailed examination of them all here, but for the purposes of this newsletter, when working on game projects I’ve learned to translate the generic term “game design” into one of the following alternative terms wherever I hear it used:

- Play Design

- Rules Design

- Product Design

- Value Design

- Experience Design

The first three of these, Play Design, Rules Design, and Product Design are what I consider the ‘Three Primary Colours‘ of game design.

Play Rules are those that apply specifically to how objects the player interacts with directly (which I typically refer to as Toys) behave. So, for example, how high a character jumps when the player presses the jump button, or how much a ball bounces when it collides with a solid surface, etc. Collectively, these rules form what I refer to as the Play Design.

Rules Design

Game Rules are those that apply specifically to the overall objective a player is trying to achieve by Playing with Toys. So, for example, whether the player has to get an object to a specific location to ‘win’, whether there is a time limit that disqualifies them from ‘winning’ if exceeded, how much ‘health’ a player loses when falling from a platform, or indeed whether the player Toy has a health variable at all. Collectively, these rules form what I refer to as the Rules Design.

A handy rule of thumb when trying to remember the difference between Play Design and Rules Design is to consider basketball. In this context the ball, players, hoops, and court are all Toys, and the way the Toys behave within the environment are all Play Rules and therefore form part of the overall Play Design. In contrast, the need to have 12 players on a team, that only 5 of those can be on court at any given time, that the hoops must be suspended at 10 feet, and that a match consists of four twelve minute quarters are all Game Rules and therefore form part of the overall Rules Design.

Mostly when people talk about game design they are talking about Game Rules, and therefore Rules Design, but it’s definitely not always so clear cut, and that has the potential to cause confusion.

Personally I find it essential to appreciate the nuances and to be able to translate where necessary, because otherwise it can be very difficult to accurately diagnose an issue when people are simply reporting that “the game isn’t fun”. Play Rules can be completely overlooked as a possible cause, particularly by less experienced game developers, because these are often provided automatically by the laws of physics and never need to be consciously considered.

How fast a player runs, how high they can jump, how bouncy a ball is – physics takes care of all that in the real world, and also in any game worlds that incorporate real-world physics by default. Not so in other games however. In certain game types all those constants suddenly turn into variables whose values need to be deliberately chosen, either to the betterment or detriment of a game’s’fun’.

The other design colours in the spectrum are every bit as important, but focus on very different parts of the experience, and so these can be less visible, especially to game developers who may spend the majority of their time on essential work at the coalface of asset creation or coding. They’re the types of design usually more visible to team members dealing with the publishing aspects of videogame development, such as producers and directors.

Product Design

Product Rules are what typically define a product’s “metagame“, which are the structures and incentives put in place specifically to reward players for continued play across multiple play sessions. Pong is one of the few examples of a commercial videogame that offers no obvious metagame. At the end of the game everything resets; no action taken by the player during a game influences anything beyond the end of the current game.

This is in contrast to later arcade games from 1976 onwards that began to include High Score tables. The inclusion of a High Score table is possibly the most basic example of deliberate Product Design. Unlike Pong, which benefited from being a two-player experience, most later arcade games were primarily single player experiences. Without the competitive nature of a two-player game to provide extrinsic motivation for ‘rematches’ there only exists the intrinsic motivation of each individual player to play again.

Game developers realised that including a High Score table meant a player’s score would be recorded and displayed in comparison to others who had played the same game. This is not a requirement of the Rules Design. For example, Space Invaders, Pac-Man, and Defender all work perfectly well without a High Score table when viewed from a Play Design and Rules Design perspective. The High Score table merely provides additional extrinsic motivation for players to play the game again. The implication of this being, from a value creation perspective, that additional plays require additional coin deposits and therefore increase revenues.

Most people today would not consider the inclusion of a High Score table in a videogame controversial in any way; however, anyone with any sort of concern regarding the ‘addictive’ nature of videogames or apps might consider studying the evolution of High Score tables. Today’s ‘compulsion loops‘ and ‘loot box mechanics‘ all have their roots in the High Score tables of arcade machines back in the mid-1970s. They all have the same underlying purpose: to amplify the intrinsic motivation that players experience to play the game again. That intrinsic motivation is a result of the Play and Rules Design layers, but the additional layer of extrinsic motivation comes almost entirely from the set of Product Rules that I collectively refer to as the Product Design.

Value Design

Value Rules are those that apply specifically to how the player exchanges value with a product. For example, whether the player pays 25c per game, $39.99 or some other amount for unlimited play, whether that amount is a one-off payment or an annual subscription, and whether it provides the player with access to all features or a limited subset of them, etc. Collectively, these rules form what I refer to as the Value Design.

Value Design is the specific area I expect to be discussing most often in my newsletter, which is why I ended up taking time to provide clarification of exactly where I see Value Design fitting within the overall spectrum of game design.

Experience Design

Experience Rules are those that apply specifically to the way in which the player is led through a game session from start to finish. That encompasses both the form it takes, as well as the functional aspects such as where a player’s attention is directed at each moment. For example, whether there is a logo screen, how long it lasts, whether it’s animated or static, how many options are displayed on the menu screen, whether there’s a menu screen at all, what moments are highlighted to the player during play, whether a “You Win” ceremony is used, etc., etc. Collectively, these rules define what I refer to as the Experience Design.

Anyone who has read my discussions of game design and production in the past will have seen me draw parallels between videogames and theatre, specifically improvisational theatre. I find theatre a useful analogue for videogames in many ways, but particularly when discussing Experience Design, because it can be much easier for people to appreciate the role of Experience Design in physical environments rather than virtual environments. In theatres the performance that takes place on the stage is an important part of the experience, but so is getting into the theatre, finding your seat, and getting out again at the end.

From an audience perspective, a great performance at 7pm in a grand theatre space feels very different from the exact same performance at 2am in a dingy warehouse space. While an actor or director may argue, passionately, that these two things are exactly the same because the performance details remain exactly the same, the holistic experience of the audience could hardly be more different.

The way I see it, Experience Design is about everything the audience experiences during the show except the performance itself, regardless of whether that show takes place within a building or a mobile phone.

For me then, appreciating the differences between Play Design, Rules Design, Product Design, Value Design, and Experience Design has become a crucial part of my skillset as a game developer. I should also be clear that, just as with the colour spectrum where there are no hard boundaries between the different colours, the same is also true with the Game Design Spectrum. All of these aspects blend into each other and can interact with one another in subtle and complex ways. It’s entirely possible for a game to be very strong in every design area except one, and yet that one design weakness can be enough to cause the game to fail in the marketplace.

I believe that by understanding the role of each type of design and the dependencies between them it becomes easier for developers to quickly recognise, diagnose, and implement solutions to many of the issues that could otherwise undermine a perfectly good videogame experience.

Thanks for taking time to consider my “Game Design Prism”. I’ve found these five “Design Lenses” consistently helpful in my own work, and I hope that next time yourself or a colleague are stuck with a game design that isn’t quite working as expected they might help unstick things for you.

TL;DR:

Game Design = Play Design + Rules Design + Product Design + Value Design + Experience Design

—