![]()

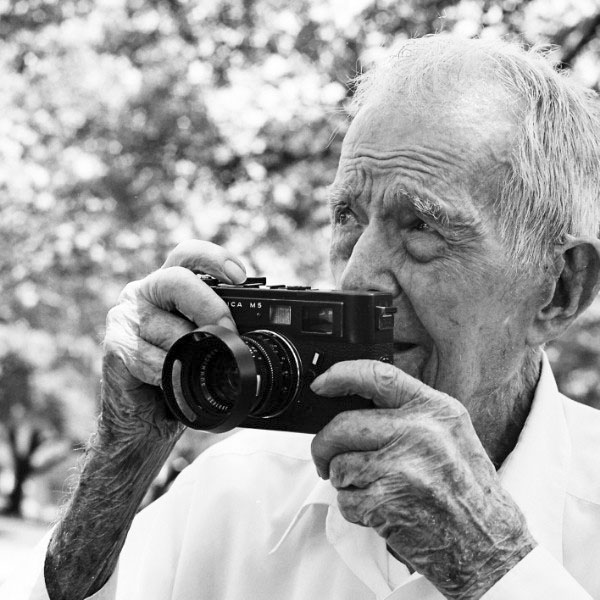

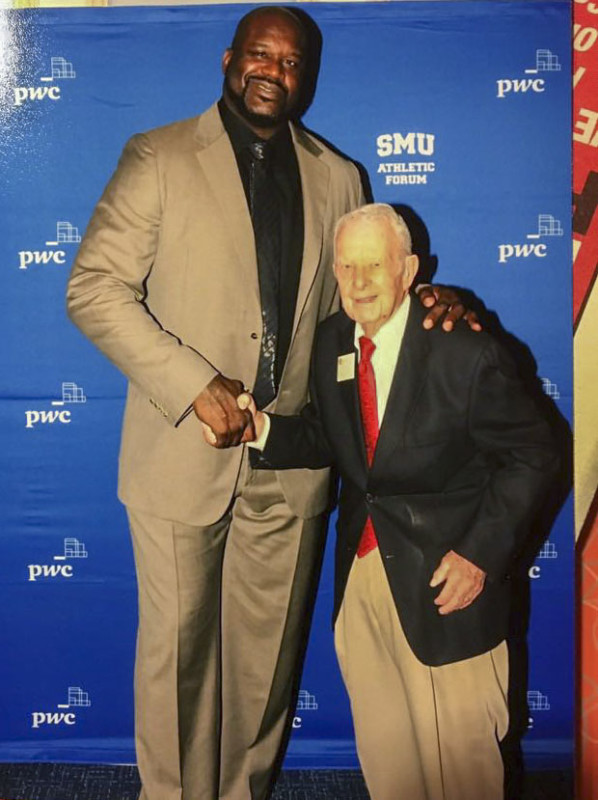

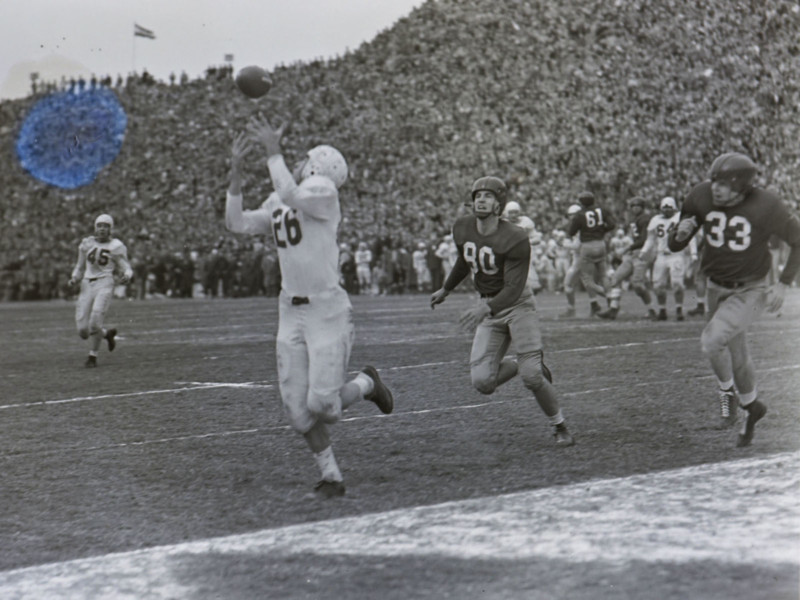

Brad Bradley photographed his first Cotton Bowl in 1948 with a Graflex Speed Graphic when he was just 26 years old. When he photographs the 87th edition of the annual college football game on January 2, 2023, he will be 100 years old, having turned a century in July 2022.

Bradley has continuously covered 74 Cotton Bowls prior to 2021, which he missed due to the COVID pandemic. He is also a member of the Cotton Bowl Hall of Fame.

Brad’s Early Years

James T. “Brad” Bradley has been known as Brad ever since he can remember. He was destined to be a farmer before World War II interrupted his plans. After joining the services, he ordered parts for B-24 bombers in the 92nd Air Depot Group. The end of the war saw Bradley, a Technical Sergeant in the US Army Air Corps, honorably discharged in 1945.

On June 2, 1946, he tied the knot with Betty Laughead, whose father, Jim Laughhead (pronounced Lawhead), was a professional sports photographer since the 1930s. To his credit, Laughhead even had a LIFE magazine cover of Audie Murphy, the most decorated soldier of WWII, where his photo assistant was his daughter Betty.

![]()

Bradley started helping out his father-in-law, who was also a photographer for a company that built B-24 bombers in Fort Worth, Texas. This mentorship helped Bradley learn the photographic ropes quickly and the two became a team.

“Most of Brad’s photo training came on the job with Laughead except for Kodak sponsored sessions focusing on color photography and architectural design,” says Floyd Stanley, who is married to Bradley’s daughter Iris.

“He [Laughead] was a good teacher,” Bradley tells PetaPixel. “He had patience with me. One of the things that I did that I was quite proud of was not only did I have the responsibility of photography but also, he tapped me on the shoulder and said go out and call on some businesses and see if we can get some work in the city of Dallas.”

This led to a long-term relationship producing newsletter photos for the Ford Motor assembly plant in Dallas.

“Huck ‘n’ Buck” Football Photography

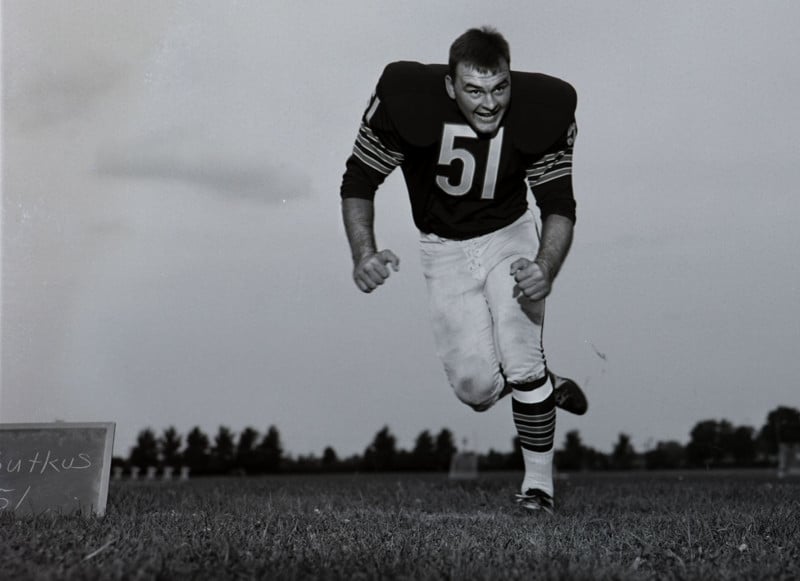

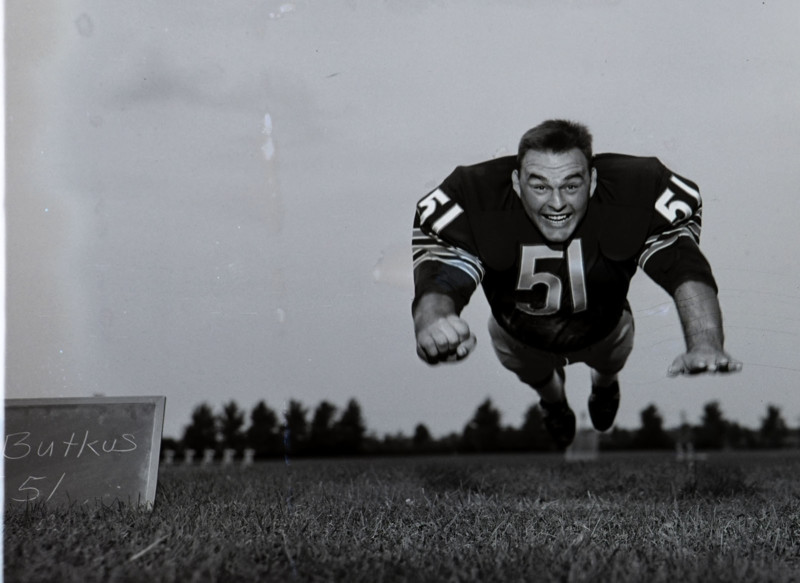

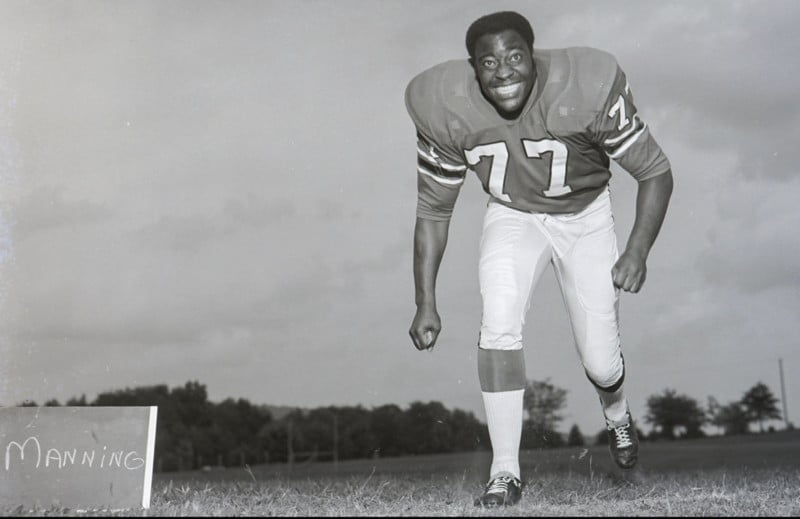

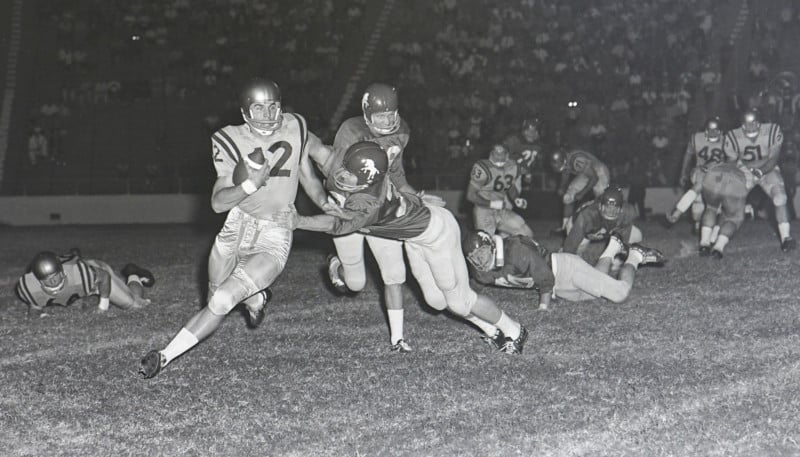

Action photography was not common in football then, and the duo started the iconic “huck ‘n’ buck” action pose for football players. This was a technique of posing athletes to appear as if they were in action.

The poses may look contrived by today’s standards, but even Sports Illustrated was running only illustrations on its cover and inside for color action images in those days.

![]()

The “huck ‘n buck” concept began when the photographic duo was shooting at Mississippi State, and one of the Bulldogs’ linebackers was having difficulty getting his footwork right for a good “posed” action pic. The photographers asked him to run laterally while crossing his legs and shifting his arms from side to side.

Progress was only made after many attempts when a teammate asked the linebacker to do the Hucklebuck Dance, which was all the rage on campuses in the 1950s.

The modern meaning of the word viral was not in use in those days, but at all football fields, photographers soon began asking their athletes to come “Huckin and Buckin.” And a perfect phrase for posed-action shots was born.

Shooting Sports with a Speed Graphic View Camera

The Speed Graphic was a press camera — a medium/large format view camera used by press photographers in the early to mid-20th century — produced by Graflex in Rochester, New York. The “speed” in the name refers to the maximum shutter speed of 1/1000 sec. using the focal plane shutter.

The camera was very slow to use. Firstly, slit width and spring tension had to be selected for the focal plane shutter. You then had to insert a film holder, open the lens shutter, cock the focal plane shutter, remove the dark slide in front of the film, focus the camera, and then click the shutter.

“You didn’t have much depth of field,” says Bradley. “Of course, because of the speed of the game, we had to use a higher [shutter] speed on the camera, and that reduces the depth of field. So, we had to anticipate where the football was going to be.

“We shot from the sideline. The only time we were ever in a different location was for an end zone play.”

Modifying Speed Graphics to Take Roll Film Holders

One of the problems was using sheet film in film holders, which allowed just two exposures per holder by flipping it after each shot. And photographers would have to carry multiple preloaded film holders onto the field.

“It was so much easier to reload after we started using 90 mm film that Kodak had,” explains the centenarian. “Of course, we had to get in a dark room to change that film. After Kodak made the 90 mm film that was exactly 4 x 5, it was possible to use it in a Speed Graphic.

“After we got the 90 mm film, our football activity was so much easier than it ever was before. It was just a miserable thing to change all the film holders before… It was kind of like a new life for us.

“The Kodak cartridge held about 75 shots, I believe. We had a guy who repaired our cameras and was also good at building things. He drilled holes into the back of our cameras, and we had screws that would hold the film cartridge up against the cameras. We had maybe a dozen of those film holders and that’s all we needed.”

SMU, Dallas Cowboys, and the NCAA

Bradley and Laughead started with SMU [Southern Methodist University] in 1947 when they got the contract to do yearbook pictures.

“Our job was to photograph the student body,” remembers Bradley. “Up until that time, Laughead had done sports for SMU, mainly football. It was a learning experience for us, and along the way, SMU was having one of its best years in football, and even though it was a lot of work, it was a great joy to be around at that time.

“That association has lasted all these years, although we don’t do as much work as we once did because they’ve added photographers to their staff.”

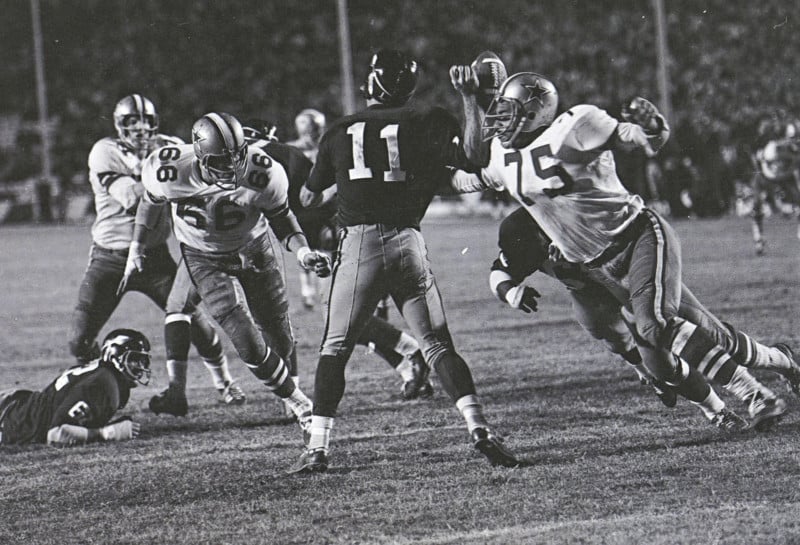

Bradley had a ring-side view of the birth of the Dallas Cowboys franchise in the 1960s. He has photographed Tex Schram, the original president and GM of the Dallas Cowboys franchise of the National Football League.

As the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) grew, so did the scope of Bradley’s work.

“During those years, my job was to go to wherever the NCAA had yearly meetings during the second week of January, after the bowl games,” Bradley says. “We went all over the entire country over a period of about 7 or 8 years. I have never enjoyed anything more than all of that because, in that process, we met people that we had worked with in football. […]”

“LSU [Louisiana State University] was primarily responsible for that [growth]. The athletic director, in about 1954, said, ‘I want to involve you more with Southeast Conference schools.’ With that, he picked up the phone and called Auburn, the second school we did after LSU. After that, Mississippi State, Ole Miss, Georgia, Georgia Tech, Florida [and more].”

Bradley has also photographed professional baseball teams, including the Cardinals, Cubs, Twins, Braves (Milwaukee), Orioles, Yankees, Red Sox, Reds, Indians, Tigers, White Sox, Senators (now the Twins), Mets, A’s, Phillies, Angels, Padres, Giants, Pirates, Giants, Dodgers, and Brewers.

The sports photographer also had an assignment of photographing President Ronald Reagan at Dallas Love Field Airport.

An Eyewitness to Integration in Football

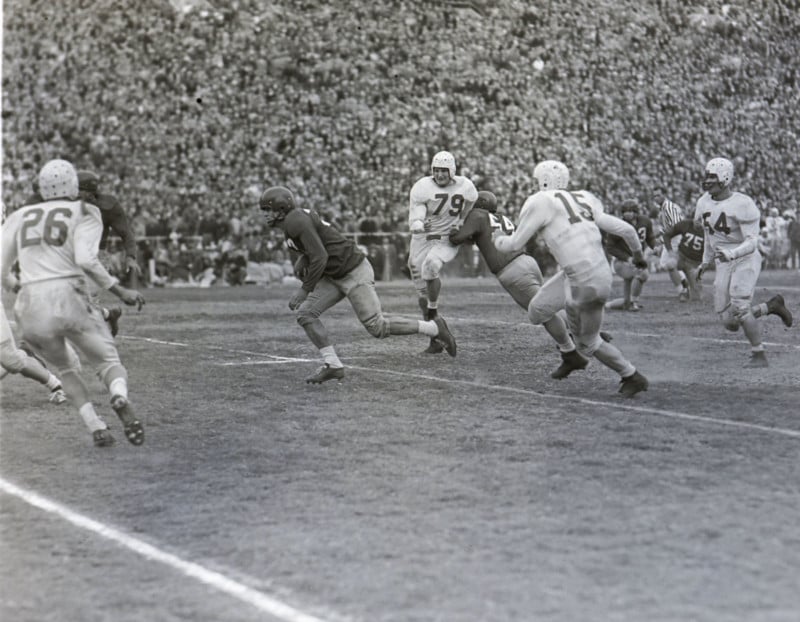

In 1948, Penn State had two Black players – Wally Triplett and Dennie Hoggard.

Triplett became the first African-American to play in the previously segregated Cotton Bowl, although he had to stay in a separate facility from the rest of his teammates because no hotels in the Dallas area would allow blacks and whites to stay together. Triplett scored the final touchdown in a 13-13 tie with SMU. – Pro Football Hall of Fame

“SMU absolutely had no concern about playing the game,” remembers Bradley. “To me, the climax was, the game was a tie, and after the game was over, both teams came back to SMU and sat down to dinner at the student union. To me, equally [great], was the way that SMU handled Jerry LeVias [first Black player in the Southwest Conference]. I thoroughly enjoyed Jerry, and I think he considers me a friend.”

When USC came to Alabama in 1970, it was the first time a fully integrated team was playing in the state.

“Alabama called me and asked me to come to the game,” says Bradley. “I remember specifically that both teams were on the field, and coach Bear Bryant was standing in one of the end zones.

“I went down there and talked to him a little bit. He was always friendly to me anyway. He told me he would be glad when the game was over. I think he somewhat dreaded playing the game. It ended up in such a way that the Southeastern Conference decided that to be more competitive, they had to recruit Black players.”

Age is Just a Number, Even When it is 100

Bradley says he owes his tremendous energy and strength at age 100 to the pleasure of his job.

“I just felt so good, so positive, about the job that we were doing that it gave me the courage to continue,” says the sports shooter. Today if I have a job in photography, I feel like it needs to be done in the best possible way.

“I was blessed with energy and strength to endure some parts of the game that were tiring. I’ve always been able to rest a little bit and then get back up and do it again.”

In 1984 New York Mayor Ed Koch organized a ticker-tape parade honoring triumphant U.S. Olympic athletes with a total medal tally of 250. Brad walked the entire parade backward as he wanted to focus on the action continuously.

Bradley’s first digital camera was the Nikon D90, but he did not shoot any sports photos with it. His first digital camera for work was the Nikon D300S.

“Last year I did the Cotton Bowl Hall of Fame induction, shot pictures in the press box at the game, did SMU Athletic Forum, Tate Lecture Series, and Doak Walker Award,” says the now digital sports photographer.

And no, Bradley has not taken up shooting photos with a smartphone… yet.

If you know other photographers still working at age 100 anywhere in the world, please let us know as we may be interested in telling their story.

About the author: Phil Mistry is a photographer and teacher based in Atlanta, GA. He started one of the first digital camera classes in New York City at The International Center of Photography in the 90s. He was the director and teacher for Sony/Popular Photography magazine’s Digital Days Workshops. You can reach him here.

Image credits: Header photo (composite) © James T. “Brad” Bradley