The most important thing you should know about Starbound is that you can play the trumpet.

At no point will this come in handy. In this procedurally generated universe of technocratic apes, evil sentient flowers and obscure and concerning monsters of many varieties, not once will the trumpet assist you in solving your problems. You can’t use it as a weapon (though there are plenty of those to be found). You can’t eat it or use it to keep warm (though you can plant a farm and warm yourself at a campfire). It is an absolutely useless trumpet. But you can team up with your friends and use it to take part in a harmonic rendition of Daft Punk’s Get Lucky, and that’s why it matters so much.

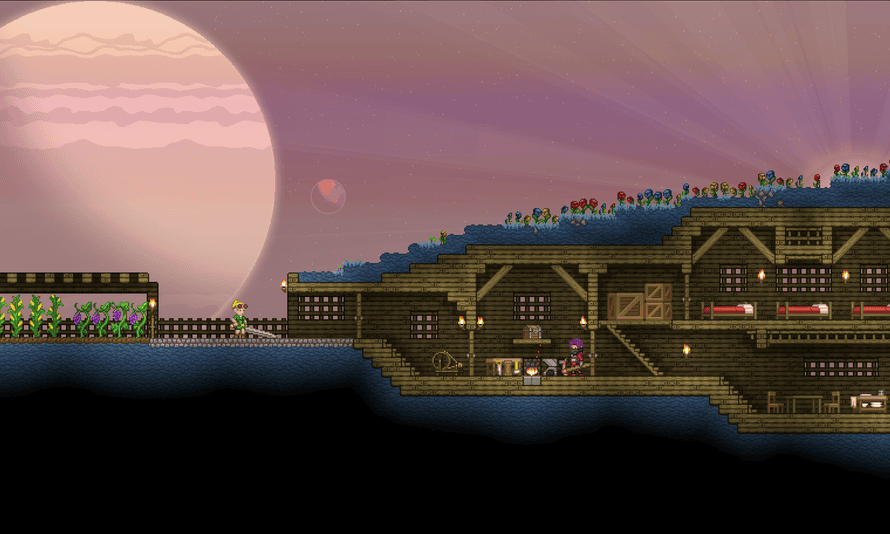

At first glance Starbound, which sold its millionth copy a couple of weeks ago despite only being available in early beta form, is all about striking out into a strange and almost unwaveringly hostile universe. Starting out with just a ship, a matter manipulator that gathers resources painfully slowly, and a vague sense of optimism, you’re given a small starting planet within a small solar system in an impossibly vast universe.

Aliens with cattle prods

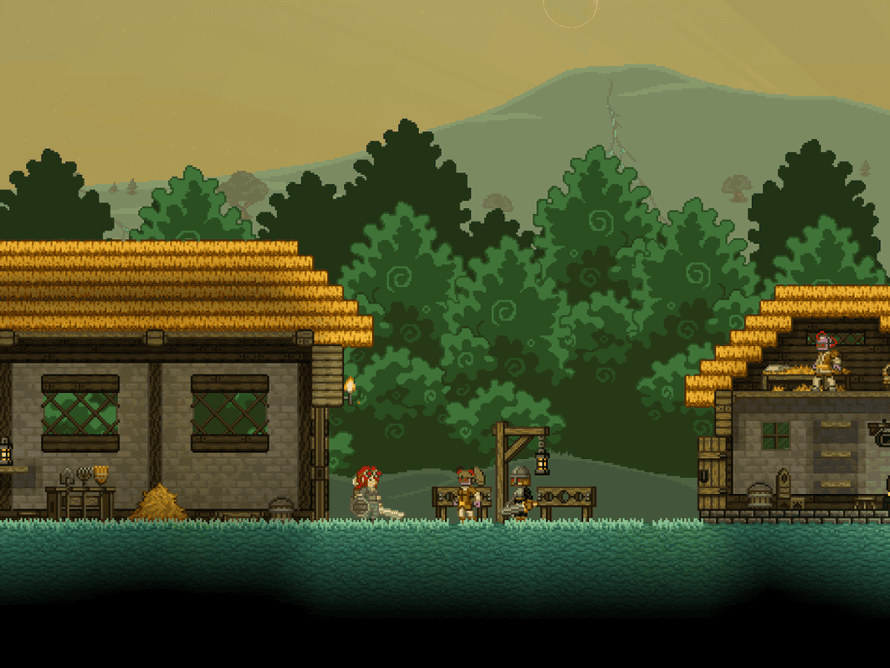

The worlds are persistent but randomised, each one distinct and fascinating. You might find a lush green forest world full of trees with eyes, or a desert world where bird-people stand guard over a mausoleum. You might find dungeons – deep underground structures full of angry floral people with cattle prods or apes with laser guns – or villages, full of similar characters but much, much less angry. You might just find a calm spot to do a bit of mining, and only later discover strange caverns of flesh deep, deep underground.

But it’s more than a game of exploration and discovery. It’s more even than a game of survival on unforgiving worlds. Like Minecraft, it’s at its most enjoyable when you can do these things with your friends, and make stories together. It’s about killing all the robots, converting their vaults into a multi-level farm, and throwing a feast for everyone who shows up. And playing the trumpet, of course.

Starbound owes a great deal to a few enormous, procedural games that have preceded it, particularly Terraria and Minecraft. And it’s proud to wear its influences on its sleeve. Community manager Molly Carroll says the comparisons are probably inevitable. “People will always draw similarities – it’s this in space or it’s that in 2D – when anything new comes out. But actually it’s becoming more of a genre. It’s not about games copying each other, but building on each other.”

Developer Bart van der Werf agrees. “I hope we would be seen as helping to define the tropes of this new genre.”

Starbound is certainly something new. It’s dizzying in its details already, to the point where simply attempting to list all the systems in the game would make this article read like a wiki entry. Along with the instrument system, there’s the hunger system, the farming and cooking abilities, and the way you get cold at night and extremely cold on moons. There’s a raft of survival mechanics layered on top of increasingly complex mining, crafting and building systems, and that’s before you get started on the procedurally generated monsters.

Lists and quests

It is an incredibly ambitious project, especially for a small team like Chucklefish, and that’s nowhere more evident than in lead developer Tiy Brice’s post last month about what the future holds for the game. From underground secrets to space combat, there’s a vast vision in that list, which is only just beginning to be realised: a huge playground, an enormous world to discover and for players to impose their own ideas upon.

The main quests, for the moment, act as incentives to explore and create certain items, and as gating mechanics, preventing you from crafting better arms and armour or from accessing harder areas of the universe until you’ve beaten particular monsters. But here too there are more ambitious plans: side quests, further elements to the main story, and a world that has to remain consistent and coherent despite its random generation and the fact that players individually will only see a small portion of what’s there.

“The largest challenge has been integrating storyline with the procedural mechanics,” says van der Werf. “We try to place things that join up with each other in the world, so that as developers you control the story and you can have a coherent whole no matter which part of it your players see. Dungeons, for instance, are made out of set blocks that fit together, so you can still control the story and keep that coherent whole. It’s a mix between full random generation and a more structured approach.”

Getting wired

There are a lot of delightful details – like the trumpet – that started out as side projects, not part of the main plan, and were included because the whole team loved them. Some are individual items, others big mechanics like the wiring system, which is currently not fully implemented, but which has already been used by players to make a digital clock and a calculator, among other things.

“I’m really proud of how the sand works,” says van der Werf. “It cascades down – it’s an old school mechanic that I haven’t seen in many games. If you hit the wrong stone on a desert planet you can collapse a whole planet of sand on top of your head and I really like that. We have been in permanent grind for a while, so taking time out to do a side project like that is a bit like taking a vacation.”

That permanent grind was necessary, van der Werf says, because of the pressures of getting the game into a playable state before Christmas. Although the development process ran badly over schedule, he says, the team didn’t scale down their ambitions for what Starbound should be. But they say they had to launch something in beta after seeing how eager their community was to play something – even if it wasn’t “finished”.

“We went for early access because we needed to launch. That was a lot of stress that didn’t have to be there, but it was an important deadline,” he says. “It’s definitely a better game for it. We are further along than we would have been otherwise. But we would have far fewer grey hairs if we had done it another way.”

“When you’re working on a game for that long it’s easy to get tunnel vision, easy to forget what the most important things to work on really are,” says Carroll. “I think early access gets you away from that and into doing what matters most for your players.”

State of play

Starbound in its current state isn’t unplayable, but there are still some rough edges – systems not implemented, limited quest lines – as well as a fair few bugs and crashes, and releasing it into the wild seems to have focussed Chucklefish on the things that matter most to their community. “We’re sticking to our original plan but if something isn’t working it’s not working,” says Carroll.

The community was so eager to get their hands on Starbound, and so engaged with what they were doing behind the scenes, that right from launch day the development team found that there were people working on mods for the game. Now there are more than 700 mods, ranging from cosmetic item sets to new races and technologies to the excellent ability to upgrade your ship. A few ideas from mods have already made it into the game itself.

“We hoped that would happen – we didn’t expect it, but we hoped,” says van der Werf. “That amount of it has really blown us away. We started out that way because we like Minecraft, and we think a lot of its community and its longevity is built on mods. From the start we have talked to the community, and that’s shaped the way we’ve done things. Some people want complicated rewrites of the game, like changing the whole thing to a 3D perspective. They’ve asked for some simple things and some things that just aren’t really possible. Things like ‘what if every character was able to walk on four legs’, which isn’t going to happen. But a lot is possible, a lot more than you’d think. I want to work with modders to take the game in hundreds of different directions. I’m excited about the potential that’s there to make whole new games and the technology challenges there too.”

Wiped out

Not everything has gone off without a hitch, and Starbound still has a sense of being slightly precarious. Early after release, there were several updates which required character and world wipes. I was one of those startled to realise my first character – DJ Beep, an intrepid robot with a small farm made from chunks of obsidian I found down a particularly deep hole – had disappeared after an early change. In response to some of the feedback, the devs have prioritised a system to minimise wipes, which might be implemented in the next update (along with a big, final character and ship wipe, and more hats). Although it’s sometimes possible to play pre-update characters, the changes to balance, physics, birds, weather, wires, quests and everything else mean that it’s easy to get left behind.

In some ways, that adds to the sense of exploration – every time I start up the game after an update, I’m finding more new additions to an already enormous world. I’ve played the early exploration game on half a dozen different updates, in the process discovering not only new planets, but also new mechanics. And if I don’t want to replay the early game again, other players have (of course) built a mod that lets me skip through the first few levels. “The character wipes gave a lot of anxiety in the community,” says van der Werf. “We can say ‘beta’ all we want but people still expect a finished game.”

The implementation of destructive meteor storms also caused some problems, with creative builders upset to discover they had landed on planets where their creations could be at risk from the weather. But on the whole, the biggest controversies have been relatively small, and the devs don’t feel the need to change everything in response to their players. “We were adding sewer dungeons to the game and we put in a monster that people didn’t really like,” says Carroll. “There’s a monster made of poop. People expected more mature humour and lore from us, I guess. They didn’t expect a poop monster. They really didn’t like the poop monster.”

And the team’s response? “We made another, bigger poop monster,” says Carroll.

Van der Werf adds: “There’s always going to be complaints about something.”